Despite the well-established adverse effects of noise pollution on human health and life, widespread breach of decibel levels continues unabated

Despite the well-established adverse effects of noise pollution on human health and life, widespread breach of decibel levels continues unabated

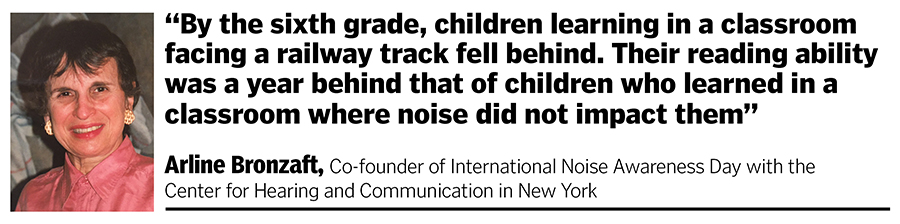

In Mumbai, a luxury skyscraper coming up next door digs deep into the bedrock. Metal crushes rock, even while under-construction buildings like this one advertise happy children, blue skies and birdsong. The advertisements say nothing of those who live in here and now of this to-be-utopia, forced to bear the health effects and disruption to their lives of noise pollution for months or years. In March 2022, newly-appointed Mumbai Police Commissioner Sanjay Pandey invited complaints on his own Whatsapp number. Among the first things he discovered was the serious impact of noise pollution on people. Within days of taking office, at his very first weekly Facebook live chat, he announced construction would not be permitted at night and on Sundays. The commissioner’s discovery of ordinary people’s distress with noise pollution is not a surprise. Forty-seven years ago, in 1975, New York-based environmental psychologist Arline Bronzaft studied the effects of noise on learning in children. In a Zoom call from New York, she told me: “My study clearly showed that, by the sixth grade, children learning in a classroom facing a railway track fell behind. Their reading ability was fully a year behind the reading abilities of children who learned in a classroom where noise did not impact them.” In Mumbai, many schools and colleges are placed next to construction sites and other noise sources. In the last two years during Covid-19 lockdowns and afterwards, ‘work from home’ has become routine and some classes continue to be held online. Pandey’s action to control noise has the ability to provide relief to people’s daily lives and bring in long-lasting systemic change. To effectively support him, we need to make our voices heard and to complain effectively against all types of noise, including the ‘unavoidable’ construction noise. In March, along with Joint Commissioner of Police (Law & Order) Vishwas Nangre-Patil, senior officers of the Mumbai Police and Awaaz Foundation, Pandey released a booklet which details effective ways to complain using a free downloadable app. Joint Commissioner of Police (Traffic) Rajvardhan Sinha commissioned 10,000 copies of the awareness booklet for distribution to schools. “I feel like giving this to my own grandchildren,” he said, turning the pages of the first printed copy. Satish K Lokhande, noise pollution expert from the CSIR-National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), who developed the free App ‘Noise Tracker’ for Android phones and ‘Noise Tracker Pro’ for iPhones, explained in the booklet: “Due to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions, noise monitoring using the conventional method was not feasible. Noise monitoring using the ‘Noise Tracker’ app with the help of volunteers proved to be a very efficient approach during Covid-19 adverse conditions.” Among those who used the free app to complain to the police against loud construction noise, Penelope Tong, a sight impaired field researcher at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) persevered through months of non-cooperation by a builder next door to her in Mahim. She measured high noise levels beyond 90 decibels, which means that she cannot work efficiently, as she cannot hear her hearing software. Mid-March, I visited Tong and used my own decibel meter to measure noise levels up to 97.2 decibels. This level far exceeds safe limits of the World Health Organization and Indian noise pollution rules. When the police visited the site a few weeks later, the noise levels were even higher: Up to 129 decibels, the equivalent of a jet engine at close quarters.  In Mumbai where noise pollution from construction is rampant, builders advertise luxury housing with blue skies and birdsong. They say nothing of their neighbours who are forced to bear excruciating noise for months or years. Image: Getty Images Mitigation measures such as noise barriers are not new technology. They were first built in California in 1968. A decade ago, I measured noise from the first barrier installed at the Bandra-Kurla Complex and found it to be highly effective, cutting noise by almost 16 decibels. In Mumbai, noise barriers are mandated under the Development Control Rules at all new flyovers, to protect residents from traffic noise. Similar barriers can be used at construction sites too. But Tong reports: “The builder categorically denied any conditions by the municipal corporation to control noise pollution. He also claimed there was no technology in existence to reduce noise from a construction site. So although the technology is available, it is not enforced or utilised on-site.” Noise absorbing barriers can reduce noise up to almost 20 decibels according to their specifications. Capped and angled barriers can even prevent sound from travelling upwards when construction is ongoing immediately next to a taller residential building. However, BMC building permissions are given without mitigation measures even though protecting health and environment are the primary responsibilities of the government. The Noise Pollution (Control & Regulation) Rules were first notified in 2000 to limit people’s exposure to environmental noise. Ten years later, in 2010, the Rules were amended to add construction as a source and limit decibels. In August 2016, in public interest litigation filed by Awaaz Foundation, the Bombay High Court ordered that “the state government shall take all measures” to restrict and abate “noise emanating from construction activities”. The court also ordered the government to file an affidavit detailing the measures it had taken in compliance of their order. Unfortunately, soon thereafter, in October 2016, while taking no action to limit decibels, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) amended their own rules to extend construction timings between 6 am to 10 pm, four hours more than previously since “there was no specific provision in the MRTP Act that prescribed to constrain the working hours. Hence the 6 am to 10 pm extended timings have been brought in to force as long as no nuisance is created to surrounding neighbourhoods.” BMC Chief Engineer (Development Plan) Vinod Chithore told The Hindu: “Today, technology is available for ensuring a reduced, if not muted, noise decibel level; for example, now only ready-mix cement is used.” Despite their statements that construction noise be controlled and remain low during construction, noise pollution is a continuous and long-term nuisance at construction sites. At the barricades of the Mumbai Metro-3, a showcase project of the government of Maharashtra, the line ‘Mumbai is Upgrading’ is prominently displayed. Behind the barricades are tall machines breaking rock; dust lines the streets and fills the air. In 2018, a complaint from filmmaker Ashwin Nagpal told me of “round-the-clock noise pollution which was impacting my sleep, health and ability to work”. I recorded up to 103.4 decibels. On orders of the Bombay High Court, the police verified that decibel levels were excessive at the Metro-3 construction site and the government assured the court that noise would be restricted. Three years later, in December 2021, Ashwin Nagpal tweeted to the Mumbai Police: “Loud Metro3 drilling machine been on from 2 am continuously at Churchgate. This is in violation of the Supreme Court order. Don’t citizens have the fundamental right to sleep in peace?”Noise pollution has been described as the new second-hand smoke. “The world’s cities must take on the cacophony of noise pollution” says an oped by UNEP Executive Director Inger Anderson in March 2022. “As cities become more crowded, their soundscapes become a global public health menace.” In his second and third Facebook live sessions, Sanjay Pandey recognised noise barriers as a solution at construction sites and gave builders until March 31 to install them. He said noise limits of 65 decibels in a residential zone would be enforced thereafter. The builder who initially told Tong that there were no available measures, now claimed he had ordered noise barriers. Tong said: “While the noise barriers have still not been effectively installed over three months down the line, I feel my struggle has at least put some pressure on the builder. The final test would of course be a reduction in the noise.” Ear-shattering noise levels at construction sites continue to be the norm all over the city. Mumbai aspires to world-class infrastructure and our construction drive is meant to fulfill that dream. Yet, our building techniques are anything but world-class. Even during lockdown, when most activities were at standstill and noise levels at an all-time low, infrastructure projects important to the government, such as the Coastal Road, continued throughout the night while noise complaints from people were ignored. These and multiple other construction projects planned under the DC Plan will last for decades. Meanwhile, recent amendments to Coastal Regulation Zone Rules have opened up the building sector, and more than 12,000 old buildings and approximately one lakh slums may be redeveloped. Many of these are placed immediately beside schools, hospitals and courts, defined as silence zones, with special need for protection under the Noise Pollution Rules. The control of noise pollution and of the Covid-19 pandemic are allied—both are serious public health crises which require appropriate management. During the pandemic, the Maharashtra government demonstrated their leadership ability to control the spread of Covid-19. Mumbai was the only urban megaopolis in India where both Covid-19 and noise pollution were controlled during the lockdowns and where citizens voluntarily celebrated important festivals and events responsibly in the interest of their own collective health. The positive effects were apparent in the lowest Covid deaths in the country as well as the quietest festival seasons in 2020 and 2021. The Global Risks Report 2022 says: “Two interlinked factors were critical for effective management of the pandemic: First, the readiness of governments to adjust and modify response strategies according to changing circumstances; and second, their ability to maintain societal trust through principled decisions and effective communication.” The government’s readiness to adjust and modify response strategies and to maintain societal trust through principled decisions on noise pollution are being tested now. The BMC, while extending work timings for construction, acknowledged that noise reduction measures were available and promised to use them. Unfortunately, their own building permissions do not even mention noise abatement as a condition.

In Mumbai where noise pollution from construction is rampant, builders advertise luxury housing with blue skies and birdsong. They say nothing of their neighbours who are forced to bear excruciating noise for months or years. Image: Getty Images Mitigation measures such as noise barriers are not new technology. They were first built in California in 1968. A decade ago, I measured noise from the first barrier installed at the Bandra-Kurla Complex and found it to be highly effective, cutting noise by almost 16 decibels. In Mumbai, noise barriers are mandated under the Development Control Rules at all new flyovers, to protect residents from traffic noise. Similar barriers can be used at construction sites too. But Tong reports: “The builder categorically denied any conditions by the municipal corporation to control noise pollution. He also claimed there was no technology in existence to reduce noise from a construction site. So although the technology is available, it is not enforced or utilised on-site.” Noise absorbing barriers can reduce noise up to almost 20 decibels according to their specifications. Capped and angled barriers can even prevent sound from travelling upwards when construction is ongoing immediately next to a taller residential building. However, BMC building permissions are given without mitigation measures even though protecting health and environment are the primary responsibilities of the government. The Noise Pollution (Control & Regulation) Rules were first notified in 2000 to limit people’s exposure to environmental noise. Ten years later, in 2010, the Rules were amended to add construction as a source and limit decibels. In August 2016, in public interest litigation filed by Awaaz Foundation, the Bombay High Court ordered that “the state government shall take all measures” to restrict and abate “noise emanating from construction activities”. The court also ordered the government to file an affidavit detailing the measures it had taken in compliance of their order. Unfortunately, soon thereafter, in October 2016, while taking no action to limit decibels, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) amended their own rules to extend construction timings between 6 am to 10 pm, four hours more than previously since “there was no specific provision in the MRTP Act that prescribed to constrain the working hours. Hence the 6 am to 10 pm extended timings have been brought in to force as long as no nuisance is created to surrounding neighbourhoods.” BMC Chief Engineer (Development Plan) Vinod Chithore told The Hindu: “Today, technology is available for ensuring a reduced, if not muted, noise decibel level; for example, now only ready-mix cement is used.” Despite their statements that construction noise be controlled and remain low during construction, noise pollution is a continuous and long-term nuisance at construction sites. At the barricades of the Mumbai Metro-3, a showcase project of the government of Maharashtra, the line ‘Mumbai is Upgrading’ is prominently displayed. Behind the barricades are tall machines breaking rock; dust lines the streets and fills the air. In 2018, a complaint from filmmaker Ashwin Nagpal told me of “round-the-clock noise pollution which was impacting my sleep, health and ability to work”. I recorded up to 103.4 decibels. On orders of the Bombay High Court, the police verified that decibel levels were excessive at the Metro-3 construction site and the government assured the court that noise would be restricted. Three years later, in December 2021, Ashwin Nagpal tweeted to the Mumbai Police: “Loud Metro3 drilling machine been on from 2 am continuously at Churchgate. This is in violation of the Supreme Court order. Don’t citizens have the fundamental right to sleep in peace?”Noise pollution has been described as the new second-hand smoke. “The world’s cities must take on the cacophony of noise pollution” says an oped by UNEP Executive Director Inger Anderson in March 2022. “As cities become more crowded, their soundscapes become a global public health menace.” In his second and third Facebook live sessions, Sanjay Pandey recognised noise barriers as a solution at construction sites and gave builders until March 31 to install them. He said noise limits of 65 decibels in a residential zone would be enforced thereafter. The builder who initially told Tong that there were no available measures, now claimed he had ordered noise barriers. Tong said: “While the noise barriers have still not been effectively installed over three months down the line, I feel my struggle has at least put some pressure on the builder. The final test would of course be a reduction in the noise.” Ear-shattering noise levels at construction sites continue to be the norm all over the city. Mumbai aspires to world-class infrastructure and our construction drive is meant to fulfill that dream. Yet, our building techniques are anything but world-class. Even during lockdown, when most activities were at standstill and noise levels at an all-time low, infrastructure projects important to the government, such as the Coastal Road, continued throughout the night while noise complaints from people were ignored. These and multiple other construction projects planned under the DC Plan will last for decades. Meanwhile, recent amendments to Coastal Regulation Zone Rules have opened up the building sector, and more than 12,000 old buildings and approximately one lakh slums may be redeveloped. Many of these are placed immediately beside schools, hospitals and courts, defined as silence zones, with special need for protection under the Noise Pollution Rules. The control of noise pollution and of the Covid-19 pandemic are allied—both are serious public health crises which require appropriate management. During the pandemic, the Maharashtra government demonstrated their leadership ability to control the spread of Covid-19. Mumbai was the only urban megaopolis in India where both Covid-19 and noise pollution were controlled during the lockdowns and where citizens voluntarily celebrated important festivals and events responsibly in the interest of their own collective health. The positive effects were apparent in the lowest Covid deaths in the country as well as the quietest festival seasons in 2020 and 2021. The Global Risks Report 2022 says: “Two interlinked factors were critical for effective management of the pandemic: First, the readiness of governments to adjust and modify response strategies according to changing circumstances; and second, their ability to maintain societal trust through principled decisions and effective communication.” The government’s readiness to adjust and modify response strategies and to maintain societal trust through principled decisions on noise pollution are being tested now. The BMC, while extending work timings for construction, acknowledged that noise reduction measures were available and promised to use them. Unfortunately, their own building permissions do not even mention noise abatement as a condition. Without binding and enforceable restraints, builders have chosen not to invest in the welfare of their neighbours. Instead, to save their own costs, they have chosen to pass on the burden to ordinary people who are forced to invest individually in noise barriers like double-glazed windows and air conditioning. Those who cannot afford such expensive measures, or choose not to use them in deference to climate imperatives, suffer noise-related ailments like high blood pressure, hearing loss, diabetes and mental health illness. They also pay through loss of productivity and extra doctor’s bills. Bronzaft’s decades-old studies on the effect of noise on children received much attention but, most importantly, her second study 40 years ago in 1982, pointed to the necessity and the way to reduce noise. “The Transit Authority decided to test out a new procedure to quiet the tracks near the school and the Board of Education installed acoustical treatment in several of the classrooms near the tracks. In 1982, I returned to the school to conduct a second study—and found that the students in classrooms adjacent to the tracks were reading at the same level as the children on the quiet side of the building.“ Encouraged by her success, in April 1996, Bronzaft worked with the Center of Hearing and Rehabilitation to institute an International Noise Awareness Day on Wednesday, 24th April. “This year it will be April 27th—it is recognised the fourth Wednesday in April,” she told me. International Noise Awareness Day has been observed in India since 2008 when the first ‘No Honking Day’ was held in Mumbai in partnership between the Mumbai Police and Awaaz Foundation and 16,000 drivers were challaned in a single day. At the end of March 2022, as Pandey’s deadline passe: for restricting decibel levels from construction, installing noise barriers and working only between 10 pm and 6 am (within the extended timings of their own rules), the government of Maharashtra dashed our hopes for peace. By an order of Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray, the government stayed Sanjay Pandey’s order. Tong called almost immediately she heard the news. “The noise is worse than ever before,” she said. In technicolour advertisements splashed across billboards and newspapers across Mumbai, idyllic surroundings and the tweet of birds in a backdrop of blue skies advertise luxury new housing. However, the residents of these same localities suffer environmental and health crises as builders cut costs to circumvent environmental safeguards while building. The government is Mumbai’s single largest builder and building is set to continue for decades. As I work from home to write this piece, metal pounds rock next door. Behind my eyes, the pounding of my headache becomes worse. (The writer is convenor, Awaaz Foundation)

Without binding and enforceable restraints, builders have chosen not to invest in the welfare of their neighbours. Instead, to save their own costs, they have chosen to pass on the burden to ordinary people who are forced to invest individually in noise barriers like double-glazed windows and air conditioning. Those who cannot afford such expensive measures, or choose not to use them in deference to climate imperatives, suffer noise-related ailments like high blood pressure, hearing loss, diabetes and mental health illness. They also pay through loss of productivity and extra doctor’s bills. Bronzaft’s decades-old studies on the effect of noise on children received much attention but, most importantly, her second study 40 years ago in 1982, pointed to the necessity and the way to reduce noise. “The Transit Authority decided to test out a new procedure to quiet the tracks near the school and the Board of Education installed acoustical treatment in several of the classrooms near the tracks. In 1982, I returned to the school to conduct a second study—and found that the students in classrooms adjacent to the tracks were reading at the same level as the children on the quiet side of the building.“ Encouraged by her success, in April 1996, Bronzaft worked with the Center of Hearing and Rehabilitation to institute an International Noise Awareness Day on Wednesday, 24th April. “This year it will be April 27th—it is recognised the fourth Wednesday in April,” she told me. International Noise Awareness Day has been observed in India since 2008 when the first ‘No Honking Day’ was held in Mumbai in partnership between the Mumbai Police and Awaaz Foundation and 16,000 drivers were challaned in a single day. At the end of March 2022, as Pandey’s deadline passe: for restricting decibel levels from construction, installing noise barriers and working only between 10 pm and 6 am (within the extended timings of their own rules), the government of Maharashtra dashed our hopes for peace. By an order of Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray, the government stayed Sanjay Pandey’s order. Tong called almost immediately she heard the news. “The noise is worse than ever before,” she said. In technicolour advertisements splashed across billboards and newspapers across Mumbai, idyllic surroundings and the tweet of birds in a backdrop of blue skies advertise luxury new housing. However, the residents of these same localities suffer environmental and health crises as builders cut costs to circumvent environmental safeguards while building. The government is Mumbai’s single largest builder and building is set to continue for decades. As I work from home to write this piece, metal pounds rock next door. Behind my eyes, the pounding of my headache becomes worse. (The writer is convenor, Awaaz Foundation)